UPDATE: Here is a functioning link for "You might be this guy. Requires a separate flowchart. "

Relationships are hard, and heartbreak is brutal. But for real, we need each other, so shut up and love.

Tuesday, January 26, 2010

Scrubs vs. Golddiggers

UPDATE: Here is a functioning link for "You might be this guy. Requires a separate flowchart. "

Thursday, January 21, 2010

Mental Illness: Part II

“Mental illness is feared and has such a stigma because it represents a reversal of what Western humans . . . have come to value as the essence of human nature.

...Because our culture so highly values . . . an illusion of self-control and control of circumstance, we become abject when contemplating mentation that seems more changeable, less restrained and less controllable, more open to outside influence, than we imagine our own to be.”

-From "The Americanization of Mental Illness" published on Jan. 8, 2010

Wednesday, January 13, 2010

Linguistics of Love Part III: Developing Dialects

Gary Chapman, an American pastor, witnessed plenty of confrontations in his family counseling practice. Couples came to him on the precipice of divorce, bitter because they still loved each other and angry because they thought that love should have been enough.

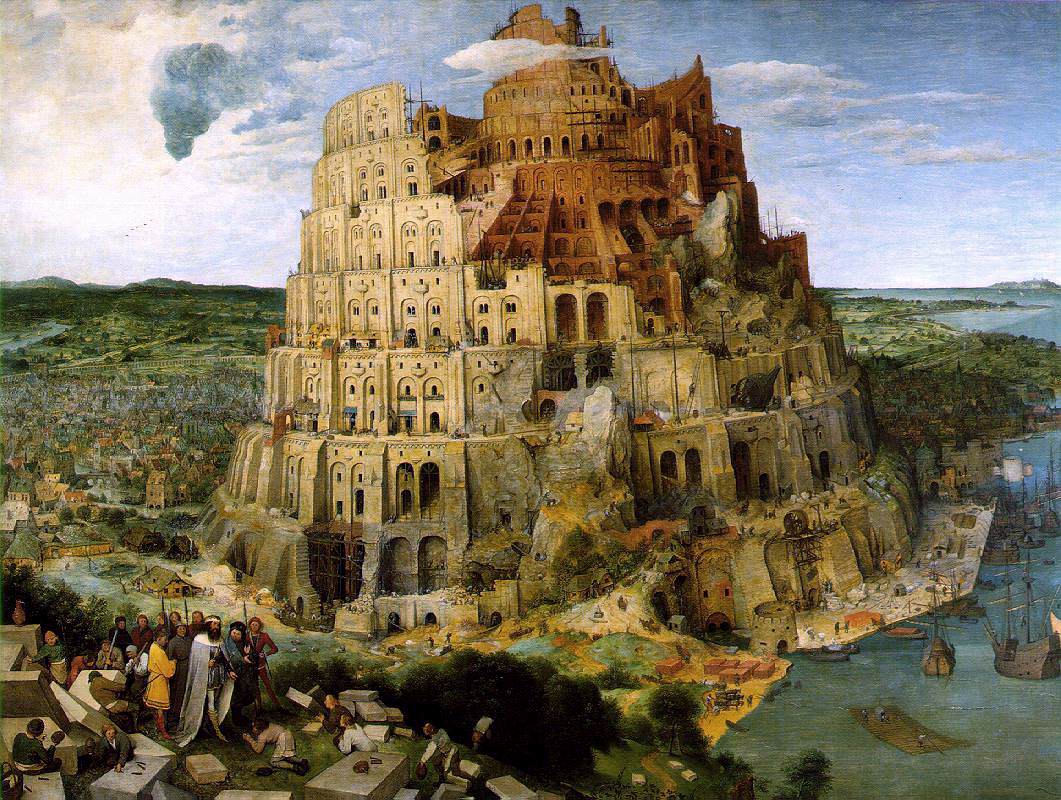

From observing these families, each a Tower of Babel unto themselves, he wrote a book The Five Love Languages which identifies five different "languages" people express and understand love: words of affirmation, touch, gifts, quality time, and acts of service. Basically, if you love someone, but you do not love them in their language, they won't understand your message and will feel suffocated without love, like a plant in a dark pantry. Conversely, if you feel suffocated, but you know that person loves you, maybe you're just not recognizing the love language they're speaking.

This point of view helped me love my friends better (not more, because I can't love them more), as I knew instantly what their love languages are. Because I like languages, I'm trying to be fluent in all five.

This understanding helped me make smarter matches, too, for myself and for others. Someone that needs words of affirmation, however, should not be fixed up with the strong silent type. I express love in acts of service, and that's great, because that's how my Beloved understands love. Lucky for me, he is very organized, so once he learned that quality time is what I need, he was able to make time together a priority even though his natural instinct is to give gifts.

He learned another love language being with me just as he perfected English in his studies in America. We've developed our own dialect with euphemisms and idiomatic expressions and gestures of love, just as my parents spoke a Vietnamese dialect borne of their inter-regional marriage, a linguistic manifestation of the compromises and shared experience that tie all couples together over time. (To my linguists: when we have kids, we'll have our own speech community.)

Love can be expressed in many ways, and that’s part of the fun. Be open to any expression.

“I love you” is expressed by “I want you” (te quiero) in Spanish, “(you) are (a) love(-source) (to me)” (suki da) in Japanese, “I love towards you” (aku cinta pada mu) in Indonesian, “I love a part of you” (!) (rakastan sinua) in Finnish, “I wish good (things to happen) to you” (ti voglio bene) in Italian, “to-me from-you love is” (mujhe tum-se pyar hê) in Hindi and many other languages spoken in India, “love I-have-you” (maite zaitut) in Basque, “to me you me-love-are” (me shen mi-kvar-khar) in Georgian (Georgia, southern Caucasus), “I I-you-love” (she ro-haihu) in Guarani (Paraguay). -A Language-Lover’s Dictionary of Languages (French edition: Paris, Plon, 2009) by linguist Claude Hagège

Love is not a prescribed set of actions. How boring would that be? It's a practice at understanding, an act as colorful, varied, surprising, and irregular as language.

Previously: Linguistics of Love Part I: Confusing the Language

Linguistics of Love Part II: Learning Another’s Language

Tuesday, January 5, 2010

Linguistics of Love Part II: Learning Another’s Language

Sometimes, learning English, I felt heady with victory at comprehension or making myself understood. I could lick the words “Zamboni machine” at the ice rink the way the other kids relished an ice cream cone. Other times, the process made me an unknowing object of derision and filled me with rage like a wild animal on a choke leash. But now I speak English, nay - LOVE English- and everything's tops.

Since Babel, every one speaks a language unto himself, and we long for someone to speak our soul fluently. Luckily, language can -with effort- be learned. The best way to acquire a new language is to learn it in terms of itself, without translation, just as monolingual native speakers acquire the language as children. Once, I found myself on Lan Yu aka Orchid Island, off the coast of Taiwan where the Yami people live; they do not speak English. When the first old man I met would point to the sky, I would try to figure out if the word he uttered meant sky, cloud, up, or grey. Rock was straightforward, as was "drink up." Usually, I got him right; sometimes, I gladly learned that I had mis-learned. But mis-learning isn't the same as NOT learning. Hell, in America, I mispronounced the verb “to iron” (I spoke it just as it’s spelled ire-run instead of i-urn) until I was 23, and I still can never remember whether I should cry over spilt beans or not.

When learning a new language, one often encounters "false friends," words that sound the same but don't mean the same thing. A well-known one is embarasada in Spanish. It means pregnant, not embarrassed. Often, there are false friends between the language that Men speak and the one that Women speak. When my brother says, "Man, my USB mouse isn't working," my boyfriend understands to help him fix it. When I say, "Man, my USB mouse isn't working," it sounds the same, but roughly translated into Manspeak, I said, "Empathize with my frustration, while I fix my USB mouse.*" (*Technology terms are the same across many languages.) I am able to translate this false friend because (a) I observed them having this conversation among their own kind and (b) I have spoken similar Woman idioms and received similarly perplexing replies in Man. (Most only have to make the mistake a few times to learn that "to be embarrassed" is "se dar vergüenza.")

Without these confrontations with confusion, comprehension cannot emerge.

Previously:

Linguistics of Love Part I: Confusing the Language

Coming up:

Linguistics of Love Part III: Developing Dialects

Sunday, January 3, 2010

Linguistics of Love Part I: Confusing the Language

{define: word} n. a speech sound, serving to communicate meaning

"Is ‘I Love You’ merely a set of sounds?" I surveyed some friends. My Beloved, whose first language is German, answered that he loves me in every language, while his roommate, who speaks English and Patois, feels that “I Love You” in either tongue doesn't have the weight he's told it's supposed to. In my own family, whose primary language is Vietnamese, we never heard the words until my father dropped me off for college. In the parking lot, he said, “I love you,” in English, as if the Vietnamese words are a curse stalking survivors of the Second Indochinese War. It seems, from my informal survey, that the meaning of love and the speech sound that represents it are no more necessarily acquainted than third cousins.

But if words cannot be counted upon to deliver even the most universal sentiments intact, how can we trust any speech? Why do I bother calling my parents or writing this blog under the long shadow of Babel?

The legend from the book of Genesis goes that the sons of Noah planned to build a tower that would reach Heaven, The Tower of Babel. To punish our arrogance, God “confused the language of the whole earth.” From then, even two workers facing each other could not communicate to move a brick, so they stopped building the city, and “the Lord scattered them abroad over the face of the whole earth.” God, doesn’t that explain so much? Now, even people ostensibly speaking the same language can feel the distance of continents between them.

Coming up:

Linguistics of Love Part II: Learning Another’s Language

Linguistics of Love Part III: Developing Dialects